This photo essay was missing from the web for quite a while, lost after a change of webhosts. I have resurrected it here. Though I made the photos in the 1980s and wrote the essay in the late '90s, it is only slightly out of date. The Los Angeles River still has a long way to go, but is improving greatly. Now bike paths adorn much of its length, and its much-desired "greening" appears to be a real possibility rather than a hope.

Once there were rivers here, crossing the inclinations of pale soil in broad meanders under the sky. But now where, long ago, crows gathered in the patterned shade of oaks there huddle the hunched backs of Nissans and Fords, and the sunlight breaks like glass against their hard curves; now where once innumerable lizards gazed out from the cloisters of the chaparral, only the dead eyes of automatic sprinklers blink expensive teardrops onto the lawns.

Once there were rivers here, crossing the inclinations of pale soil in broad meanders under the sky. But now where, long ago, crows gathered in the patterned shade of oaks there huddle the hunched backs of Nissans and Fords, and the sunlight breaks like glass against their hard curves; now where once innumerable lizards gazed out from the cloisters of the chaparral, only the dead eyes of automatic sprinklers blink expensive teardrops onto the lawns.

Today soil is bought in bags at windowless emporiums and sequestered in ceramic cellblocks on apartment balcony or suburban porch, and the earth once nurtured by millenia of tender rains lies underneath the asphalt of roads, mutely asphyxiating.

Roofs, streets, parking lots, reject the gift of heaven and spit the rain away into gutters and drains. And these drains empty into what were once called rivers. For though few believe it, once there really were rivers here: where now there are only the shapes of rivers. Just as a prisoner is no longer a man but only the shape of a man, constrained by rules and walls and wires and re-formed into a crucible for alternations of stupor and rage, all his energies wasted, so with what once were rivers here, in Los Angeles, in this city on a desert plain by the sea.

Roofs, streets, parking lots, reject the gift of heaven and spit the rain away into gutters and drains. And these drains empty into what were once called rivers. For though few believe it, once there really were rivers here: where now there are only the shapes of rivers. Just as a prisoner is no longer a man but only the shape of a man, constrained by rules and walls and wires and re-formed into a crucible for alternations of stupor and rage, all his energies wasted, so with what once were rivers here, in Los Angeles, in this city on a desert plain by the sea.

The people came, and the people built. The land was cheap, and every man and every woman desired to own a piece of the earth. The sellers sold and the buyers bought, and the land hardened under possession like the heart of a slave. The rains waited, and the sellers sold clear skies and pieces of the earth, and fences went up and papers were signed, and it was repeated again and again and again.

Soon, houses were built, and roads to those houses, and stores were built, and roads to those stores, and factories and warehouses were built, and roads to those factories and warehouses, and the land became expensive. But there was always more land in the wide valleys, and the sellers sold and the buyers bought their pieces of the earth, and they spread their fences and houses and stores and factories and roads in swarming multitudes.

Soon, houses were built, and roads to those houses, and stores were built, and roads to those stores, and factories and warehouses were built, and roads to those factories and warehouses, and the land became expensive. But there was always more land in the wide valleys, and the sellers sold and the buyers bought their pieces of the earth, and they spread their fences and houses and stores and factories and roads in swarming multitudes.

Eventually, the rains came down, the gift of heaven clattered against the roofs and the roads and the parking lots, and the soil underneath stayed dry. And since the soil could no longer take up the water, there were floods. In 1938, when the big floods came, the people blamed the river that could not contain those waters. In anger, fear, and blindness, they punished the river and imprisoned it in high gray walls, so that it would be forced to carry the ever-greater burden of the water that could no longer soak into the earth.

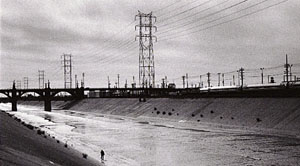

This is how a river became an oversized drain, carrying away the waters that once soaked into the soils and replenished the aquifers that feed the city wells. Now the city imports water from mountains two, three, or four hundred miles away, while on any stormy weekend enough rain flows down the concrete trench of the Los Angeles River to supply the entire city with water for a year.

This is how a river became an oversized drain, carrying away the waters that once soaked into the soils and replenished the aquifers that feed the city wells. Now the city imports water from mountains two, three, or four hundred miles away, while on any stormy weekend enough rain flows down the concrete trench of the Los Angeles River to supply the entire city with water for a year.

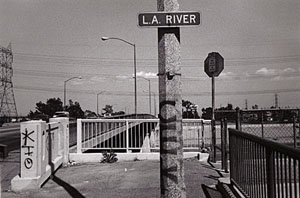

It is likely that there is no other river on the earth that is as rigidly shackled as this, the Los Angeles River. Channeled, walled, fenced in, and dammed, sunken down out of sight and sound of the city, sequestered between power pylons and patchy asphalt maintenance roads, it has become at once a joke and a legend in its city. People have lived near it for twenty years and never known it exists, even as they drive along or over it in the metal isolation of their cars. Gang members sneak into it to paint their names on its walls, or to shoot each other. Schoolchildren ride their bikes along it to watch the winter floodwaters rumble by, then they slip in and drown. The Metropolitan Transit Authority sends its newly-hired bus drivers down into it to practice turns. It's the Empty Quarter of the city, bleak and forbidding, dangerous and unknown, unpopulated but not uninhabited. It is, at present, a subtraction, a place from which everything has been taken away. It is both the heart of the city and the symbol of a city with no heart.

Among the careless, it evokes derision or at best pity, but among a few it engenders a sort of love, and not just for what it once had been: traffic noise does not descend to it, so it is the only quiet place in a noisy city; it is the only uncrowded place in a busy town; it is the only place where there are no cars. In many ways this concrete abstraction of a river is the only place in the city where one can feel the light and air and silence of the desert, the reverberant solitude that has made of deserts holy places for so many of our species.

Among the careless, it evokes derision or at best pity, but among a few it engenders a sort of love, and not just for what it once had been: traffic noise does not descend to it, so it is the only quiet place in a noisy city; it is the only uncrowded place in a busy town; it is the only place where there are no cars. In many ways this concrete abstraction of a river is the only place in the city where one can feel the light and air and silence of the desert, the reverberant solitude that has made of deserts holy places for so many of our species.

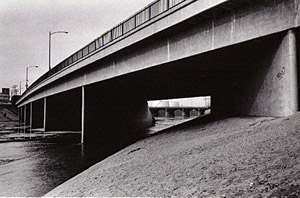

In spite of all the concrete, the shabby industry, the buzzing powerlines, the fumes spilling from the overarching roads, there remain instances of elegance, of earthy richness, even of beauty, along this trammeled and insulted waterway. Once, long ago, bridges were built not just to carry traffic but also to enliven the eye and heart of the passerby; these bridges and their arches and filigrees remain, often alongside of strong-of-back-but-dull-of-wit descendants. The city that turns its back on history has steadily been spending money to strengthen and restore them.

Farther downstream, at the mouth of its estuary, the river complicates the lights that shine from bridges, docks, and cranes and turns a concatenation of wharf and waterfront into a sensation of grace. In Long Beach, a signature park faces the river from one bank, apartments and a tourist zone from the other.

Farther downstream, at the mouth of its estuary, the river complicates the lights that shine from bridges, docks, and cranes and turns a concatenation of wharf and waterfront into a sensation of grace. In Long Beach, a signature park faces the river from one bank, apartments and a tourist zone from the other.

And here and there along its length, the river becomes a river for a while. At Sepulveda Dam, there is a park designed to fill during winter storms, holding back the full force of the rains; the water soaks into the soil for a few brief days till it's released into the concrete trench downstream, but in the marshy channels behind the dam, egrets and herons stalk among the reeds, ducks paddle, fishes leap and splash.

By Glendale, alongside of Atwater, and at a place called Frogtown, again the river bottom is unpaved, reeds, shrubs, and even large trees grow, birds call at dawn and at dusk, and the eyes and souls of human beings can find a moment of animal peace.

By Glendale, alongside of Atwater, and at a place called Frogtown, again the river bottom is unpaved, reeds, shrubs, and even large trees grow, birds call at dawn and at dusk, and the eyes and souls of human beings can find a moment of animal peace.

There are plans afoot to break down some of the walls, rip up the concrete, build more settling basins that can be lakes in winter and parks or farms the rest of the year. The river may be able to live as a river once more, some of the land at least can live as land and not just a platform for our vanities, and you and I will be able to walk on a riverbank again, and hear birdcalls echoing into the dusk. For a river that was so long ago falsely convicted and unjustly imprisoned that it's barely even remembered as a river, freedom is becoming possible.

Text and photos by Richard Risemberg, sometime in the 1990s