Introduction

Discussions about bicycle facilities tend to focus on bike routes, bike lanes, bike paths, "sharrows," and intersections. Inside observers know that cycling enthusiasts are often divided, and divisive, over the merits of these facilities on, adjacent to, or in replacement of streets. Urban planners often adopt these paint markings and path designs to show how "bike friendly" their designs and design company are. But what's left out? Bike parking!

A case in point comes from the January-February 2011 issue of American Bicyclist, a publication of the League of American Bicyclists. The lead article in the "Engineering" category is on "Complete Streets." It starts on page 14, and goes for seven paragraphs, and all the way to page 15, before parking is mentioned at all--and then only in the context of amenities businesses can provide to bicycle commuting staff. It's only in paragraph eight that parking for bike riders in general is addressed. The final reference to the entire issue of bicycle parking in that article is at the end of the ninth paragraph. Yet, the simple concept of a rack where you can lean and lock a bike is a concept that a lot of communities and employers forget.

Engineering, in the context of bicycle advocacy, has almost universally meant places to ride. Putting "bicycle parking" in a search engine often leads off with "hits" for motor vehicle parking lots next to bicycle paths. Seldom have questions about places to stop reached the attention of traffic engineers. It seems that bicycles are still perceived, if unconsciously, as toys. The dominant concept is that people ride their bikes to ride their bikes. Destinations for cyclists are seldom considered, except in the context of planning and placing a bike route, lane, path, "sharrows" or other riding facilities. Occasionally, in commercial and retail developments, some space might be set aside, somewhere, for a rack or two. This is because the center operators or business owners, unlike most public traffic planners, see their establishments as potential destinations for cyclists.

Motor vehicle operators usually find their parking is provided for in street or local infrastructure design. When "they" plan a road or street, "they" plan for motor vehicle parking as well. Who plans for cyclists? This isn't a rhetorical question--even though the answer is usually "nobody in particular." For our first sample of bicycle parking planning, please take a look at the racks in the photos below. One is in in San Diego's Balboa Park (near the Spreckles Organ Pavilion).The observant may have noted these four sets of frame-holding upright brackets don't look like most commercially available bicycle parking. The bent steel rod stock is thinner than the more usual shaped hollow tubing or pipe. The wooden base for this installation is also not standard. Commercially available bike racks generally use concrete bases, or steel fixtures, to hold the racks themselves upright. The other bike rack is next to a forty-five place motor vehicle parking lot, in Presidio Park, also in San Diego. It features eleven bike wheel slots in an artistic modifications of the wheel-bending "grid" style rack. It's also near a drinking fountain.

Both were put in place by the Boy Scouts.

On the one hand, motorists and the community at large would not stand for essential and vital infrastructure being supplied by youth group service projects, using donated materials, based on nonstandard and amateurish designs. On the other hand, it is rare that Eagle Scout projects create motor vehicle parking. When they do, it is normally at a trail head, campsite, or some other remote location. You won't expect to find youth groups voluntarily paying for, or soliciting contributions of materials for, paving projects in historically significant, long-established metropolitan parks in the midst of the seventh largest city in the United States! The conclusion: Bicycle parking, historically, has not been seen as essential and vital infrastructure.

Let's return for a moment to the varied rack design. Even when two different racks come from two elements of the same umbrella organization, there's a divergence in the design of bicycle parking that wouldn't be tolerated in motor vehicle facilities. Motor vehicle facilities are standardized, right down to the paint color--straight while lines or white-outlined rectangles for parking stalls, blue painted lines or outlined rectangles for handicapped spaces. That's it. Let's perform a thought experiment here: Imagine a parking lot where the stalls, and spacing between the motor vehicle stalls, are marked by zigzagged orange lines. Would anyone park there, or would most motorists just be confused?

There's another lesson here, too. The Balboa Park Eagle Scout rack, for four or more bicycles, takes less than the space for one subcompact car. The Presidio Park Eagle Scout rack puts eleven bike slots into the space needed for parking two subcompacts. Further, no particular provision is made for access--because none is really needed. Simply step from a sidewalk, lift bikes over a curb, wheel along a patch of lawn, all preexisting and unmodified, and you'll be at these racks. Compared to a whole parking lot, or even a motor vehicle parking space and the necessary pavement for access to that space, installing a rack or two takes little or no new paving resources.

Why parity is a distant dream

A casual view of modern US cityscapes and suburban areas shows a tremendous outlay of resources for "free" motor vehicle parking. Frequently as much as half of a roadway is devoted to on-street parking and clearance between parked vehicles and moving traffic. Commercial and residential developments are accompanied by parking lots and garages. This is designed into the planning process, as it has been for generations. There is an expectation, often codified into state or municipal laws, enunciated in zoning provisions, and stated in building permits, that there shall be a specified amount of parking on the street, in provided lots, or attached parking structures. Exceptions may, on occasion, be made in reference to the quantity of parking associated with each project or apartment building, but the principle remains: You build a building, you'll have to have parking. Even where motor vehicle parking is not going to be free, the rates are lower than the costs. For example, I was recently quoted one per-spot construction price for a downtown San Diego parking structure of $20,000 (a verbal communication in 2011).

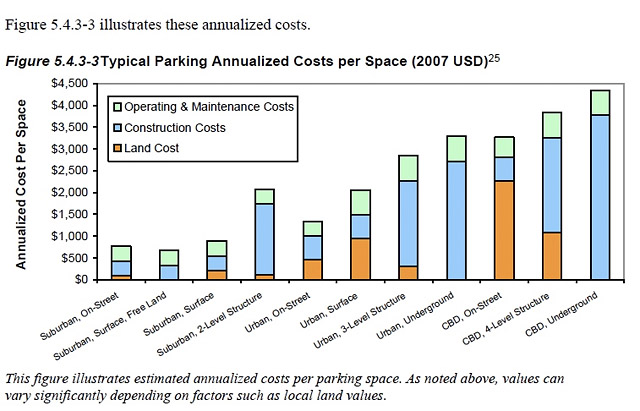

The following is a more graphic assertion of the sums routinely spent, without much question or considered justification, on motor vehicle parking.

The JPEG image referenced above is originally from this Canadian study, which references costs and expenses in many US cities. This study demonstrates an incredibly important factor in this discussion. Motor vehicle parking space costs are seen as invisible, unless someone is cursing a parking meter. Even where we know land costs are high, such as in densely used urban cores and downtowns, we don't like paying for parking, if only because it's "free" somewhere else. We usually don't even ask for what other purposes might we use that land--n other words, the "opportunity cost" of providing "free" parking. Land devoted to parking is often treated as having no opportunity costs, so the only costs of increasing supply are construction and maintenance expenses (as in the above referenced study).

The study also demonstrates those construction and maintenance costs are themselves considerable drains on either the public or private purse. The roads don't pay for themselves--property taxes, sales taxes, and other general funds resources are typically spent on road construction and maintenance. The information here references a Texas Department of Transportation document from 2006, but it applies generally in the US. Federal and state gas taxes don't fully pay for the roads, and even if they did, they wouldn't necessarily be used for local roads. Instead, other funding mechanisms, including the use of local municipality general funds, derived from property, sales, business, and other taxes and fees, are used for road construction and maintenance. This includes the construction and maintenance of on-street parking.

For example, I live in San Diego County, where we have an additional 0.05% sales tax to fund a regional transportation initiative called TransNet. During the 60 year life of the program, more than $17 billion will be generated and distributed among highway, transit, and local road projects in approximately equal thirds. As a "car-free" cyclist, but local spender, I subsidize highway developments from which I'm barred, and transit capital investments for systems that historically have had, and currently have, little or insufficient accommodation for cyclists. For example, Metropolitan Transit System buses have racks that can accommodate two bikes on the front. San Diego Trolley policy is to allow only two bicycles per trolley car, except during "rush hour," when only one bicycle is allowed.

In a return to Canadian material: Victoria, Canada, installed a bike corral downtown back in 2007. The $20,000 spent on the covered rack provides a covered space providing parking for up to 23 cyclists. Though there's a general reluctance for businesses to give up any on-street parking for anything other than cars, the corral simply brings more customers into this commercial zone.

But the basic point here isn't how inexpensive bicycle parking is per space, compared to motor vehicle parking. It isn't even that space meant for parking one motor vehicle could accommodate many, many more bicyclists. The point is that public mass bike parking facilities are so unusual they're newsworthy.

Even on a one or two bike basis, purpose-built parking facilities for bikes are rare in comparison to motor vehicle facilities. Even in the most-densely used urban core areas, it's unusual to see dedicated cycle parking facilities in quantity. In fact, the example pictured at left, of an installation of dozens of racks makes political sense to San Diego residents only because it is across the street from La Jolla High School, whose rich legacy of endowed construction and facilities has apparently left no room on campus for a bicycle cage. Go Vikings!

Even on a one or two bike basis, purpose-built parking facilities for bikes are rare in comparison to motor vehicle facilities. Even in the most-densely used urban core areas, it's unusual to see dedicated cycle parking facilities in quantity. In fact, the example pictured at left, of an installation of dozens of racks makes political sense to San Diego residents only because it is across the street from La Jolla High School, whose rich legacy of endowed construction and facilities has apparently left no room on campus for a bicycle cage. Go Vikings!

This array of bike racks is not unique, even in San Diego. However, almost all the other examples I've seen are adjacent to the beach, at public libraries, or on the grounds of school and college campuses. The sole "on a sidewalk in a business area" bike rack array near this magnitude I've seen in town is outside a gym that's three blocks away from the beach. I'm unaware of any public, commercial area, urban core locations in San Diego that host such an array of bike locking brackets. Even recreation centers within the City of San Diego don't have this large an installed inventory of bicycle racks, although they come closer to the stock routinely placed outside libraries than any other government facility.

Creating an inventory of on-street bicycle parking that would meet ten percent of the existing on-street or surface lot motor vehicle parking (which is a small but probably attainable percentage) isn't going to happen quickly. Diverting paved street parking spaces for motor vehicles for the self-powered set en masse plan probably won't happen. Ever. Sadly, one of the reasons is economic. It is admittedly an extreme case, but the City of San Diego's arrears on street maintenance are more than a third of a billion dollars. Even assuming a low, low price of $100 per bike place for purchasing, placing, and installing on-street bicycle parking fixtures, new public bicycle parking facilities for a mere 125,000 employees, students, shoppers and diners (out of a population of 1.25 million) in one go is a sudden budget blip of $12,500,000. It wouldn't happen. You can use the same sort of back-of-the-envelope math in your own town or community. A drive to increase the stock of public bicycle parking as one quick project isn't politically possible. Another reason is psychological--people are enormously attached to their parking spots. In fact, one way to help with approval of "road diets" and other traffic calming and ordering measures is to create plans that increase the motor vehicle parking in a given area.

What is possible is setting goals for future expansion, construction, and other projects. The idea is to build into the existing design and approval processes the explicit understanding that, in the future, public bicycle parking will be a necessary precondition for permits and licenses, and zoning variances. It's the same slow way our current vast inventory of motor vehicle parking lots were created: Over the course of decades, as part and parcel of each neighborhood and development's growth and planning.

Bicycle parking supports "utility" cycling

Many devoted cycling enthusiasts ride primarily for recreation, leisure, and sporting pursuits. This is fine, but it isn't necessarily the sort of riding that best benefits our communities or ourselves. A simple ride to and from the grocery store, the bank, or the library can provide the daily dose of physical activity recommended by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Riding a bike on level ground or with few hills is included in their list of moderate-intensity aerobic activities. If you've a predisposition for Type 2 Diabetes, physical activity is a key to preventing or delaying its onset. Even if you have the autoimmune disorder colloquially known as Type 1 Diabetes, physical activity is a key element in most treatment plans (consult with your Certified Diabetes Educator, physician, or Endocrinologist if you'd like to know more).

It's not just the Center for Disease Control down in Atlanta that has an interest in physical activity. According to this report from the website Alaskabikehub.com, The SouthEast Alaska Regional Health Consortium (SEARHC) is pleased to have played a role in Sitka's becoming an official Bicycle Friendly Community. SEARHC's interest in cycling comes from their interest in institutionalizing physical activity, according to the report. Sitka has placed bike parking racks to encourage riding by giving riders facilities at destinations.

Showing Them the Money

I'd like to apologize for this section. Ideally, it would be filled with links to fact-filled studies of the effects provided bicycle parking has on retail business, dining, and housing pricing. Apparently, I'm too early, as there are surveys and studies in progress in some areas. However, the effects of bicycle parking alone are seldom studied. Instead, we have sweeping assertions of the economic impact of "bicycle friendly" areas. The quotation below is from the referenced article.

What many cities in Europe have found out, is that pedestrians and cyclists are better shoppers than those who arrive in automobiles. They are more able to stop on a whim, browse casually, and for those who don't own a car, the fact that they aren't spending loads on owning and operating an automobile all the time means they potentially have more money to spend. Many major shopping districts in European cities are car-free, and they thrive.

[Editor's Note: Also see "The Bottom Line Speaks" and "Bucking the Cycle" in this magazine.]

We can clarify this discussion by focusing on a specific bicycle parking installation for a moment: the Bike Corral, where a "motor vehicle" parking space is converted to bicycle parking, either temporarily or permanently. I've anecdotal verbal evidence that bears this out. For example, in private discussions, board members of the San Diego County Bicycle Coalition have mentioned that several businesses in the Gaslamp Business Improvement District fervently desire a "bike corral," but the hold-up is developing engineering and placement standards for converting a motor vehicle parking space into something else, especially with rigid installations in that "something else."

In Portland, OR, there's a page on a local news website highlighting the businesses which benefit from bike corrals. From Bend, OR, an article on the Bike Around Bend website highlights a local business owner's efforts in privately funding a bike corral on his very crowded street. From Datwyler's perspective, the fact the City didn't contribute to funding the installation of the corral isn't a sign that the City wasn't enthusiastic about the project, but rather a reflection of Bend's current economic straits. Part of the project's appeal for the City was to help alleviate the bike parking congestion in the area. A Los Angeles area news website, www.laist.com, in their article about Los Angeles' first bicycle corral (which is now in place!), prominently mentions the nearest business when describing its planned location: "[I]n front of Cafe de Leche on York Boulevard at Avenue 50." Moving on to Seattle, the news site My Ballard features an article by "Geeky Swedes" about "Bike corral installed at Jolly Roger Taproom" which explicitly states George Hancock, the owner of Maritime Brewery and the Jolly Roger Taproom, tells us that they first talked with SDOT about installing a bike corral earlier this year when they were trying to figure out bike parking at their new location. Again, this bike parking was installed because the neighboring business owner wanted it installed.

Such websites as Big Green Boulder have noted an increase in parked bikes following the growth in on-street fixtures. The author follows the money: Think about that as a business. If your business is located somewhere with very limited parking--let's say, downtown Boulder--would you rather have one car parked outside, or 12 bikes? The safe bet is that 12 customers are better than however many fit in that hypothetical car.

The observant may have noticed businesses that want bicycle corrals tend to self-select themselves from areas where utility cycling is already commonplace. However, there are many businesses that feel reducing the on-street inventory of motor vehicle parking in favor of on-street bicycle parking are worthwhile. And it's not only bike shops that are leading this charge.

The Good, the Bad, and the Weird: A photo gallery

Below, you can see where a shopping center in the Linda Vista area of San Diego has placed their rack. This ribbon rack would, under normal circumstances and adequate clearance, support six or more carefully locked individual bicycles. However, it's been cemented into place close to a wall. Properly installed, it would have been able to support two bikes, or more if folks use a cable lock and lock up together.

Below, you can see where a shopping center in the Linda Vista area of San Diego has placed their rack. This ribbon rack would, under normal circumstances and adequate clearance, support six or more carefully locked individual bicycles. However, it's been cemented into place close to a wall. Properly installed, it would have been able to support two bikes, or more if folks use a cable lock and lock up together.

Sometimes folks feel that since the bike rack is placed out of the way, anything else that should be out of the way should go right there. It's not like someone's going to want to park a bike, right? In theory, this might be fine -- stuff that shouldn't be kept on a sidewalk anyway shouldn't obstruct wheelchair ramps and other access. In practice, it diminishes the effectiveness of an installed rack, often when there's plenty of unused space where that bulky object wouldn't inconvenience any others.

Sometimes folks feel that since the bike rack is placed out of the way, anything else that should be out of the way should go right there. It's not like someone's going to want to park a bike, right? In theory, this might be fine -- stuff that shouldn't be kept on a sidewalk anyway shouldn't obstruct wheelchair ramps and other access. In practice, it diminishes the effectiveness of an installed rack, often when there's plenty of unused space where that bulky object wouldn't inconvenience any others.

On occasion, even other bicycles parked on a rack can be an inconvenience. This example hasn't moved from a nice U bracket (at the intersection of Cass Street and Garnet Avenue in Pacific Beach) for several months. If it were a plumber's truck, with big colorful graphics and advertising all over, it would have been towed for being parked on the street too long. As it is, this junker and its zip-tied sign have been taking prime corner bike parking space that would easily accommodate two bikes for quite a while. If I were the proprietors of the sushi place right there at that corner, I'd be miffed.

On occasion, even other bicycles parked on a rack can be an inconvenience. This example hasn't moved from a nice U bracket (at the intersection of Cass Street and Garnet Avenue in Pacific Beach) for several months. If it were a plumber's truck, with big colorful graphics and advertising all over, it would have been towed for being parked on the street too long. As it is, this junker and its zip-tied sign have been taking prime corner bike parking space that would easily accommodate two bikes for quite a while. If I were the proprietors of the sushi place right there at that corner, I'd be miffed.

Sometimes, even with the best of intentions, a merchant, landlord, or shopping center manager just can't win when it comes to bike racks. One example is the backside parking rack at the Trader Joe's market in Pacific Beach. The folks in charge of the parking lot know that it's a really small parking lot, and that a great many of their customers and employees ride bikes to the location. Unfortunately, their hands are tied by the municipal mandate to maximize auto parking in a lot that is, frankly, inadequate. The initial result was this ribbon rack, set on a safety island and abutting a heavily buttressed light standard. Even though everyone knows the light standard reduces the capacity of that rack, they really had no other place to put it.

Sometimes, even with the best of intentions, a merchant, landlord, or shopping center manager just can't win when it comes to bike racks. One example is the backside parking rack at the Trader Joe's market in Pacific Beach. The folks in charge of the parking lot know that it's a really small parking lot, and that a great many of their customers and employees ride bikes to the location. Unfortunately, their hands are tied by the municipal mandate to maximize auto parking in a lot that is, frankly, inadequate. The initial result was this ribbon rack, set on a safety island and abutting a heavily buttressed light standard. Even though everyone knows the light standard reduces the capacity of that rack, they really had no other place to put it.

Unfortunately, this lot is, for many reasons, the scene of atrocious driving. The management ultimately had to put in a veritable Maginot Line of cement-filled steel bollards. This further reduced the capacity of that ribbon rack.

One interesting side effect of other street developments is the opportunity they present for increasing bicycle parking capacity. A case in point is the traffic calming on First Street in downtown San Jose. To accompany a "bulb out" at one intersection, the city engineers took advantage of the new creation of otherwise unused already paved space to install this curly ribbon rack. You can just see some of the "Original Joe's" across the street, but I suspect most of this rack's patrons are more likely to patronize the "Cafe Trieste" coffeehouse, also just across the street. I imagine there's considerable traffic between this location and the nearby San Jose State University campus.

One of my local shopping centers started with essentially no racks. They must have gotten tired of riders locking up to the many railings along the wheelchair access ramps, because they added these grid racks.

One of my local shopping centers started with essentially no racks. They must have gotten tired of riders locking up to the many railings along the wheelchair access ramps, because they added these grid racks.

The managers must have been monitoring the use of these racks, and asking other questions. Why? Because after a few months, these attractive little pennyfarthing bike shaped racks started popping up on otherwise unused spaces, near store entrances, around the center. Not only are they useable, they're also near where people would want to park their bikes!

Motor vehicle parking is often planned for peak parking demands. For example, sports stadia used by professional teams, or intended for professional teams, are usually surrounded by acres of blacktop that are entirely unused most of the time, or occasionally rented out for swap meets. Given that, you'd think such locations as Java Depot in Solana Beach, a favored rendezvous point for group bicycle rides, would have plenty of bicycle parking facilities Instead, this is what happens.

This sort of bicycle parking goes on all weekend at this location. Also during the week, for the retired weekday riding warriors, and local workers and residents who ride to caffeine. One would think the landlords, after more than a decade of this, would do something about providing bicycle parking facilities. Frankly, they don't have much spare space to work with. It still looks ridiculous -- even if the available parking spaces on the left were all filled with certified carpooling motorists, they'd only reach parity, perhaps, with the cyclists whose steeds are lined up on the right, or sheltered within the overhanging alcoves, or dangerously laid against plate glass windows.

Previously, I wrote that a single municipal or county project to create a ten percent match of cycle parking to motor vehicle parking wasn't likely. What is likely is single projects to add bicycle parking on streets where cycling is undergoing a renaissance. Doing a whole municipality in one go can be too much, but a more localized plan concentrating on areas where cyclists have already achieved a certain density is more easily justified. In San Diego, several of those neighborhoods are in the "uptown" area, including Hillcrest, Normal Heights, Adams Avenue, North Park, and South Park. Recently, work crews put in new bicycle parking facilities along or near much of Adams Avenue.

Previously, I wrote that a single municipal or county project to create a ten percent match of cycle parking to motor vehicle parking wasn't likely. What is likely is single projects to add bicycle parking on streets where cycling is undergoing a renaissance. Doing a whole municipality in one go can be too much, but a more localized plan concentrating on areas where cyclists have already achieved a certain density is more easily justified. In San Diego, several of those neighborhoods are in the "uptown" area, including Hillcrest, Normal Heights, Adams Avenue, North Park, and South Park. Recently, work crews put in new bicycle parking facilities along or near much of Adams Avenue.

Here's the brand new bicycle parking bracket in front of the John Adams Post Office.

Oddly, the yoga studio located across the street from the Post Office was deemed worthy of two new bike parking brackets, even though the proprietors had already set out two grid racks for the convenience of their customers.

Conclusion

Bicycle parking is an often-overlooked amenity. Unlike motor vehicle parking, or even bicycle travel facilities such as paths, lanes, and routes, bicycle parking is underfunded and understudied, if studied at all. There are few systematic surveys of the subject. That said, there are specific locations where proponents, residents, and commercial tenants favor bicycle parking facilities. These include:

- Retail and dining destination locations:

- Shopping centers

- Restaurants, bars, and cafes

- Bicycle-friendly businesses, including but not exclusively bike shops

- Public parks and picnic areas

- Libraries and recreation centers

- Elementary, Middle, and High Schools

- Neighborhoods known (or notorious!) for a large number of bicycle riders

- Requirements for justification far beyond that needed for motor vehicle parking

- Idiosyncratic bike rack designs, made without reference to standards

- Continued use of outdated rack designs

- Ineffective and inefficient bike rack placement, also often due to a lack of standards

- Financing obstacles

- Public health and fitness advocates and institutions

- Traffic planners and transit authorities interested in traffic calming and road diets

- Retail merchants and eating place proprietors

- Educators or others interested in enhancing the mobility of people too young to drive

- New developments and buildings (through permit and licensing processes)

- Redevelopment, revitalization, and conversion of existing developed areas

- Infill of street bicycle parking racks, brackets, and parking meter mounted loops through partnerships with business improvement districts and other local merchant and landlord associations

The resulting progress may be slow and frustrating. Without individual and localized examples of good (and bad!) bike parking, showing its value as a public amenity and role in neighborhood vitality, it will be difficult to create institutional, broad spectrum change, or even public bike parking envy. And to park your bike when youg et somewhere.

But the time to start is now.