by Wade Eide

Montréal's Promenade de la

Commune is a bicycle-friendly street. But don't expect to be able to ride

along at high speeds, as you can usually do on other major streets in the

city. At least not on a weekend afternoon in the summer. What was once

a mono-functional arterial street has now become a very pleasant tree-lined

river-front promenade, where the movement of vehicles is not its only raison-d'être.

In fact, on a sunny Sunday in mid-summer, vehicular traffic definitely

takes second place to strollers, families, in-line skaters, horse-drawn

"caleches" and eventually even to waiters crossing the street to serve

patrons at tables under the trees of the promenade. Definitely not a street

for would-be road racers.

Montréal's Promenade de la

Commune is a bicycle-friendly street. But don't expect to be able to ride

along at high speeds, as you can usually do on other major streets in the

city. At least not on a weekend afternoon in the summer. What was once

a mono-functional arterial street has now become a very pleasant tree-lined

river-front promenade, where the movement of vehicles is not its only raison-d'être.

In fact, on a sunny Sunday in mid-summer, vehicular traffic definitely

takes second place to strollers, families, in-line skaters, horse-drawn

"caleches" and eventually even to waiters crossing the street to serve

patrons at tables under the trees of the promenade. Definitely not a street

for would-be road racers.

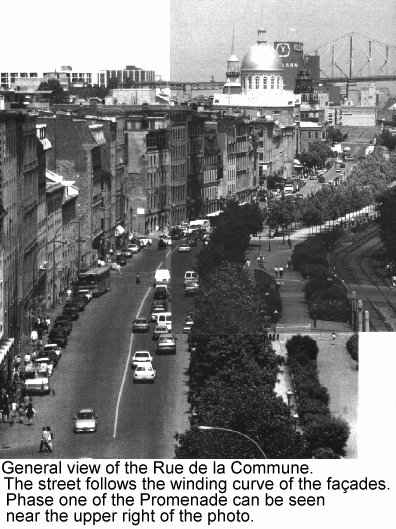

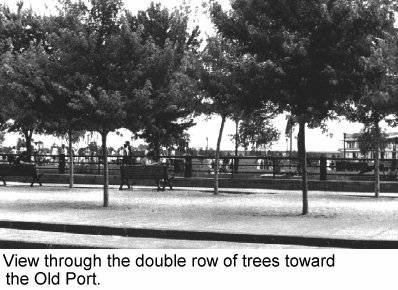

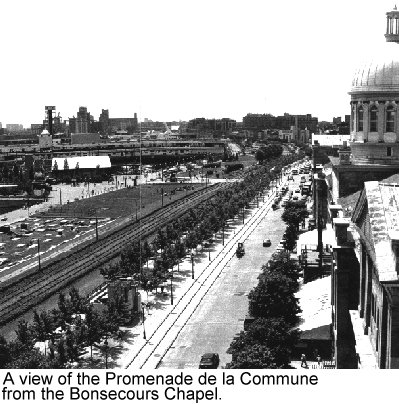

The promenade is a ribbon of granite that follows the winding curve of the 19th century grey stone façades of Old Montréal, marking the limit between the once-fortified city and the St. Lawrence River. The simple parallel curves of its geometry reflect the alignment of the façades and heightens our awareness of the character of the place. Restaurants take advantage of the wide sidewalk in front of their establishments to set up tables. Across the narrow carriageway are three stepped sidewalks leading up to the wide pedestrian promenade in the centre of which are shade trees planted in two parallel rows. The raised promenade allows people strolling beside the low wall and steel tube handrail at its southern edge to enjoy the view over the Old Port and the river.

Phase one of the Promenade de la Commune was completed in 1992, just in time for the celebrations of the 350th anniversary of the founding of Montréal. The concept for the project was the result of a "charrette" (an intensive workshop session) led by architects Melvin Charney, Peter Rose and Aurèle Cardinal. The conceptual plan was adopted by the City in 1991. The objectives were quite simple:

- Re-establish the river-front façade of the city, a façade made up of individual buildings built on the vestiges of the fortifications that were demolished in the 19th century;

- Establish a visual relationship between the Rue de la Commune and the Old Port and the river;

- Transform what had been the old city's "back yard" and a traffic artery into a place of conviviality oriented primarily to pedestrians;

- Encourage the restoration of the buildings lining the street.

These goals were eventually materialised in the definitive project in the following way:

- The planting of trees at a distance of 23 metres from the façades in order to create an appropriate scale for the street and to allow the appreciation of the buildings as a whole;

- The widening of the north side sidewalk to four metres;

- The raising of the level of the south part of the promenade in order to facilitate views toward the Old Port and the river.

- The narrowing of the carriage way to a uniform 11 metres in order to permit:

- slow two-way circulation;

- pedestrians to cross safely anywhere along the promenade;

- parking on the north side only, leaving the south side unencumbered and thus preserving a spatial relationship between the promenade and the Old-Port to the south.

A Clash of Cultures

The project was realised beginning in the summer of 1991 by the Public

Works Department of the City according to the working drawings produced

by the newly-formed Urban Projects Bureau, under the direction of architect

Alan Knight. The project did not proceed without numerous controversies

and internal battles that persisted even after completion of the work.

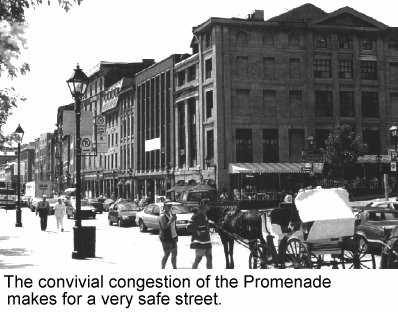

A clash of cultures, the culture of urban architectural know-how on the

one hand, the culture of the traffic engineers on the other. The idea of

a project that would narrow the roadway in order to force vehicles to move

more slowly, a project that would even deliberately produce a situation

of congestion with a chaotic but convivial mix of pedestrians, cyclists,

caleches, buses and cars is completely anathema to the modern culture of

traffic engineering -- even in the case of the promenade project where

a co-ordinated effort was to be made to divert the fast through traffic

from the Rue de la Commune to other parallel streets. Happily however,

through sheer persistence (and some political arm wrestling) the project

was built pretty much in conformity with its conceptual principles.

Perhaps not unexpectedly, the traffic engineers found an ally in the

local bike lane advocates. Until the construction of the promenade, there

had been a segregated bicycle lane along the street, confined to an alley

visually cut off from the street by hedges on one side and from the Old

Port by a tall fence on the other. The guiding urban principle of the promenade

project was (and is) the mix of people, the multiplicity of functions and

the hierarchical mix of different types of circulation: pedestrians / cyclists / caleches / buses / cars. The pedestrian is king in this hierarchy, and

can enjoy the comfort and safety of the granite-paved sidewalks, while

not putting his life in peril when he crosses the carriageway. Cyclists

and motorists take second place. The designers in the Urban Projects Bureau

recognised that the bicycle is a vehicle and that the safety of cyclists

is best served by allowing them to circulate freely in normal vehicular

traffic, following the same rules of conduct as other drivers of vehicles.

The safety of cyclists, of even the inexperienced and less competent ones,

would certainly not be jeopardised in the promenade, where traffic is forced

to move very slowly during times of high congestion. At other times, width

of the traffic lanes leaves ample room for bike-car lane sharing. The bike

lane advocates and their supporters at the City wanted some sort of a return

to the status quo, arguing that the link between the existing segregated

bi-directional bike lane that joins the Rue de la Commune at its eastern

end, and the multi-functional recreational Canal de Lachine path at its

western extremity must not be broken. Eventually, a sort of compromise

was reached, and it was decided that a clear system of signs would be installed,

informing cyclists on the bike paths that they must stay on the carriageway of the Promenade de la Commune, using it as a shared roadway, or directing

them to an alternative route through the grounds of the Old Port. None

of those signs were put in place and a certain ambiguity persists, at least

for less experienced cyclists.

Perhaps not unexpectedly, the traffic engineers found an ally in the

local bike lane advocates. Until the construction of the promenade, there

had been a segregated bicycle lane along the street, confined to an alley

visually cut off from the street by hedges on one side and from the Old

Port by a tall fence on the other. The guiding urban principle of the promenade

project was (and is) the mix of people, the multiplicity of functions and

the hierarchical mix of different types of circulation: pedestrians / cyclists / caleches / buses / cars. The pedestrian is king in this hierarchy, and

can enjoy the comfort and safety of the granite-paved sidewalks, while

not putting his life in peril when he crosses the carriageway. Cyclists

and motorists take second place. The designers in the Urban Projects Bureau

recognised that the bicycle is a vehicle and that the safety of cyclists

is best served by allowing them to circulate freely in normal vehicular

traffic, following the same rules of conduct as other drivers of vehicles.

The safety of cyclists, of even the inexperienced and less competent ones,

would certainly not be jeopardised in the promenade, where traffic is forced

to move very slowly during times of high congestion. At other times, width

of the traffic lanes leaves ample room for bike-car lane sharing. The bike

lane advocates and their supporters at the City wanted some sort of a return

to the status quo, arguing that the link between the existing segregated

bi-directional bike lane that joins the Rue de la Commune at its eastern

end, and the multi-functional recreational Canal de Lachine path at its

western extremity must not be broken. Eventually, a sort of compromise

was reached, and it was decided that a clear system of signs would be installed,

informing cyclists on the bike paths that they must stay on the carriageway of the Promenade de la Commune, using it as a shared roadway, or directing

them to an alternative route through the grounds of the Old Port. None

of those signs were put in place and a certain ambiguity persists, at least

for less experienced cyclists.

Success

The principles embodied in the project -- the mix of functions and people,

the culture of congestion, the pleasure of seeing, the pleasure of movement,

the pleasure of variety, the comfort and simplicity of the design -- have

made the Promenade de la Commune a cultural and a commercial success. The

many hundreds of thousands of people that visit Old Montréal and

the Old Port every year now include the the Rue de la Commune in their

experience. Businesses and cafés along the promenade are thriving.

Many new boutiques and restaurants have opened since the summer of 1992.

The Promenade the la Commune is a quintessential urban project, embracing urban values, realised with urban know-how. But the funny thing is, the majority of the "tourists" that frequent it and enjoy it, as well as the old city and the Old Port, are in fact people from the automobile suburbs around Montréal.

Wade Eide is an architect

with the Montréal architectural firm, Atelier

BRAQ. From 1991 to 1993, Mr. Eide worked in the Urban Projects Bureau

at the City of Montréal,

where he was a member of the Promenade de la Commune project team.

Illustrations for this article are from a study prepared by Atelier

BRAQ and Saint-Denis, architectes paysagistes for -- and with the collaboration

of -- the Urbanism Service of the City of Montréal.