Review by Bicycle Fixation (July 2012)

A few weeks ago, we were preparing to commence a long-awaited train trip through the west: out across the deserts on the Southwest Chief to northern New Mexico, a short bus hop up to Denver, where Gina's sister lives with her husband, and then the California Zephyr back to San Francisco for a few days. We'd wind it up by taking the Coast Starlight home along the hills, cliffs, valleys, and beaches of the California coast, one of our favorite rides. We booked roomettes for the overnight portions of the trip. The Amtrak website makes planning the transport itself fairly easy—in fact we played with various travel dates to find the better deal, since they too now use "dynamic pricing." But one question came up that no website could help us with: how to get about once we were there—wherever the "there" might be.

More specifically: since this trip would take the entire Bicycle Fixation staff out on the road (part of our purpose being to record bicycle infrastructure in the cities we were visiting), the question was, No bikes? Standard bikes? Folding bikes?

All the trains we were taking, plus the one bus (operated by Greyhound but contracted by Amtrak) would accept full-sized bikes in the Amtrak bike boxes, which don't require full disassembly of the bike, only the removal of the pedals and the turning of the handlebars by ninety degrees. They also require that you be boarding and leaving the train at a station that has baggage service, but that was not a problem in our case. (Some smaller stations don't have baggage service.) However, two of our trains left fairly early in the morning, and packing standard bikes does take about half an hour, meaning getting to the station earlier than need be, and in towns where we are not familiar with the public transit schedules.

So we were inclined to folders, the obvious best choice for this trip. Amtrak lets you carry small-wheeled folders onto the train and stow them in any of the capacious luggage compartments that are standard on both sleeper cars and coaches. The problem was, we owned only one folder between us, and it was a rather crappy one at that—an older, heavy, sluggish Dahon bought on clearance years ago, and one that had no particular inclination to stay folded no matter how sternly you admonished it.

Furthermore, Gina had borrowed a Brompton for a week from our friends at Clever Cycles when she visited Portland a few years ago, and she fell in love with the eccentric little British bikes.

The solution: I leaned on a couple of long-suffering associates in the LA bike world, gentlemen who happened to run bike shops and were Brompton dealers...with demos on hand. And so, thanks to Josef at Flying Pigeon LA, we scored a Brompton M6 with click-on front bag for Gina, and thanks to Kyle at Silverlake's hippest bike shop, Golden Saddle Cyclery, I ended up with a beautiful, sporty S6L-X, with titanium bits to lighten it, and even the telescoping seat post, which at six-foot-one I mightily appreciated. I transferred a saddlebag from one of my own bikes to the Brooks, we shipped some office clothes via the Post Office to SF for a couple of client meetings Gina had scheduled there, and after stuffing everything else into very large courier bags, we saddled up and headed down to the subway stop three miles away, and thence to Union Station for the first leg of our trip.

Gina had ridden Bromptons before, and I had ridden both bikes back from their respective shops after getting to them via Metro, so we didn't need any miles to acclimatize ourselves to the little fellows. We did need some exposure to the double-takes they engendered in anyone who saw them fold from fairly noticeable bicycles, with their long seatposts and (non-adjustable) stems, into a tiny cluster of cables, wheels, and struts that you can easily heft in one hand.

Our first victim was an Amtrak employee whom I accosted for some information on the boarding procedure for the Southwest Chief. I had swung the rear triangle under to prop the bike up—in effect, it becomes its own kickstand—and, after answering my question, the fellow said, "Is that your bike? You'll need to go to the baggage room and get a box."

To which I answered, "Just watch." I pulled a latch or two, swung some bits around, and in about five seconds the bike had largely disappeared, leaving a tidy confusion of metallic bits with a saddle sticking out of it—clearly something one could stow with ease aboard the sleeper car. The station agent's eyes bugged out of his head, and somewhere behind us several bemused onlookers broke out into applause.

The applause, we were to learn, would not be an isolated occurrence.

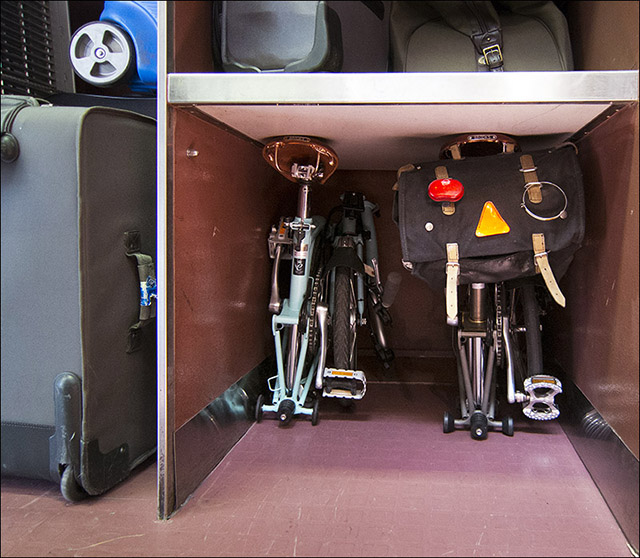

There isn't at present a direct train from Los Angeles to Denver, so we rode the Southwest Chief as far as Raton, New Mexico, where we picked up a bus connection to denver. More often, Amtrak operates its own buses, which are about as good as buses get in the US, but this connection was contracted out to Greyhound. The bikes fit into the bus luggage bay fine, though they had to lie on their sides, and we got on and began our journey northwards.

Now, you can't accuse Greyhound of age discrimination, as our driver seemed to be upwards of a hundred years old, and talked to himself most of the way. Still, he was an affable fellow when he noticed you, and fell asleep only once during the four-hour drive, when the handy rumble strips on the roadside woke him up. It was an uneventful trip, livened up by a thunderstorm flashing over the foothills of the Rockies to the west, but when we arrived at Denver the driver mistily informed us that we were stopping at a temporary station, as Denver's grand original Union Station was being refurbished, and that the temporary light rail stop was a few blocks away for now. No problem; we unfolded the Bromptons and pedaled off through the evening to the indicated location.

Where we discovered that the baseball game had finished a short while earlier, and the E Line train that would take us to the in-laws' suburb was packed Tokyo-solid. No problem, though; we collapsed the Bromptons back down and hoisted them up the (inexplicable) four steps to the railcar, where once again they were the center of attention.

The in-laws have bicycles and do take the train occasionally but still see life from the windshield perspective; they were waiting for us at the light rail station with an SUV into which we loaded the Bromptons for the half-mile traverse to their building. Though we had unfolded them when we had gotten to the station—they are easier to roll than to carry, especially when you are wearing a messenger bag—we were getting pretty good at the transformation by then, and it was no trouble to collapse them again for the long drive home.

By the time we arrived, two or three minutes later, it was late, and we went right to bed after some minor socializing.

I had the next day set aside for exploring and photographing Denver's bicycle facilities, and the S6L-X got a good workout carrying me around. I first took a spin around Greenwood Village and its fellow, the Denver Technology Center across the freeway. There wasn't much to see—the usual brownish modernist towers you see in office parks all over the farther suburbs, made contemporary with rounded corners, but at least there were bike racks in front of several of them—and even a few bikes in them! After considerable searching, I found the entrance to a truly handsome pedestrian bridge that I knew led back to the light rail station and waited for a train to take me back to the city center.

A ride back downtown on a post-rush-hour E Line train didn't require a full fold, and the much less crowded train (as well as the fact that it was now daylight) afforded me a chance to look out at the unfamiliar town. Though all of Denver's considerable outskirts are lanky sprawling duplicates of LA's suburbs, I did catch glimpses of bike racks at stations and adjacent buildings, and even a B-Cycle docking station or two. As we drew nearer to downtown, the number of bicycles and bicycle facilities increased exponentially, with lanes and sharrows making appearances on most larger cross streets, and bike racks more in evidence. I rode the E Line all the way back to the temporary Amtrak stop and commenced wandering over as much of Denver's core as I could manage in the few hours I had.

This is where I discovered the value of a Brompton as social artifact. Basically, if you don't want attention, this may not be the bike for you. Everybody loves them, even if they don't see you work the fold. Young men and women, construction workers, office drones, old ladies, even drivers of pickup trucks...everyone finds a Brompton irresistibly cute and feels compelled to smile, wave, call you over, and comment. And if they see you folding or unfolding it, they will—after they put their eyes back into their heads— flood you with questions on its origins, ride, price, and where the heck they can get one for themselves. It's like walking around with a puppy—albeit one that converts from pup to hound and back at a gesture. You will make friends.

As a bike, the Bromton proved eminently serviceable. The steering was lighter than I cared for, but other than that it behaved well. I rode it over smooth streets and broken, uphill and down, along tranquil river paths and through heavy traffic on busy streets, and with the wind on every quarter. That first day in Denver I probably rode it thirty miles or so, including a long slog along the Platte River bike path back towards our home base, and then east along a wide busy street filled with typical speed-demon suburban drivers. While it took more effort than I would have needed to expend had I had my lithe little 20-pund fixie, it was as good as most bikes out there and better than many. And once back in our small guest suite, it folded down to nearly nothing and hid in the closet.

The next day the in-laws took us along a stretch of the High Line Trail, a mostly-unpaved path that follows an old and now unused irrigation canal. Much of it winds between the backyards of exurban neighborhoods, with occasional forays into the street and, once, over a flood-control dam. Most of it is heavily wooded and lush with reeds, grasses, and occasionally flowers, and it dips into a couple of local parks. Much to my surprise, both Bromptons handled the hardpack very well despite tiny wheels and, in my case, slick tires. After an hour and a half, a thunderstorm appeared to be brewing, and as we had left raingear at home, we cut the ride short. We did enjoy several peaceful miles on a bucolic trail—and learned a bit more about the Brompton's capabilities.

The next day, well-practiced at folding and unfolding the little bikes, we bade the in-laws farewell, climbed on the light rail, and headed to the train station in downtown Denver. Since the California Zephyr was running a bit late, we had time to take a spin along Cherry Creek and around the growing loft district, where we found a coffeehouse. Gina had not had a chance to see Denver itself, since we'd gotten in at night and immediately headed to the suburbs, and she had a fine time pootling about the the lanes and paths (and sipping real coffeehouse coffee). Of course the Bromptons drew smiles and queries from all and sundry every time we stopped long enough for people to work themselves up to a greeting.

I tested the Brompton on three occasions, years apart. The first was in Portland, Oregon, for two days in autumn (with a shout out to the good folks at Clever Cycles for the very generous loaner). The second was a more extensive Los Angeles-Denver-San Francisco-Los Angeles train/bike tour, followed by a month of riding around my home turf. (With an equally enthusiastic shout out to the gracious proprietor of Flying Pigeon LA in Highland Park.)

My average ride was one to five miles, once or twice a day. Sight-seeing and commuting, with one longer ride of about twenty miles.

The Brompton is breezy. After weeks of thinking about how to describe it, "breezy" seems best to me, because it makes your life feels easy—even lighter—when you have it. Even when it's unfolded, getting it in and out of the garage, bus, or train is simple. A breeze.

This seems to defy logic and even physics, because for one to ride a bike it has to be about "so-tall" and about "yea-long" to match my body, right? All my bicycles meet these criteria. Yet the Brompton‐tall enough and wide enough—slips through places when my mixte and diamond-frame bikes struggle.

The geometry pros out there will tell me that the Brompton is shorter with smaller wheels. Okay, but the point is that it slips through clutter like it was Teflon.

Pedaling hither and thither is a breeze, too. In Portland I found myself cycling through the gears quickly as I accelerated across the Steel Bridge with calls of "Hey, slow down!" trailing off behind me. Was I going so fast? I am not a particularly strong rider, and to find myself speeding caught me by surprise.

Around Portland I visited the Chinese gardens, various coffee shops, a chocolate shop, and a restaurant on the bicycle. The Brompton made it easy. Folded, it would sit by my seat as I ate. At the garden it tucked away in a corner under the diligent, and enchanted, eye of the volunteer at the ticket booth. Conversely, imagine for a moment sitting at a sidewalk cafe, away from any bike rack, with your big bicycle next to you like a fence.

For the second test I had the dedicated satchel option. A sturdy, copious shoulder bag that slips easily into a small plastic bracket on the head tube. This I fully tested, filling every pouch, internal and external, with plenty of urban stuff: laptop, power supply, books, pens, mobile devices, purse stuff, shoes, and more. Mounted, the bag became part of the bike, never rattling or feeling loose. The bike's handling changed noticeably with the weight, but not inappropriately.

On the train it was so easy to fit the Brompton in the carry-on shelves of the sleeper or coach cars. No taller than a roller bag, it tucked away neatly. In Denver I rode a firmly-packed dirt trail with more ease than I would have thought, given the upright riding position, small wheels, and street tires. in San Francisco I easily (for me) climbed the considerable slopes (that no doubt pass for modest hills there) with the front bag fully loaded. On a ride to Sausalito I crossed the Golden Gate Bridge in a gale (that no doubt passes for a gentle breeze there), took the ferry to the Embarcadaro, and rode back to our room in the Fillmore. During the ride it was just like having my big bike with me. During stops it was much better. Traveling is certainly a breeze with the Brompton.

Near the end of the test period (after I had in fact bought the bike for myself), I folded the bike into my Mini Cooper (it fits sitting up, by the hatch, perfectly) and drove it to work. After work, in my office clothes, I busted out the Brompton, hopped the bus, and met Rick in Santa Monica. There we rode to a cookbook signing at Cafe Luxxe and rode back to the bus stop to retrace my route home. To me this was the ultimate test: car/bus/bike in office clothes. And the Brompton passed. In addition to all the benefits mentioned above working together beautifully, its open design allowed me to get on and off in officeclothes easily. This trip would be impossible with my big bikes. Even if I had a rack on the car the trip would be a headache.

Now: are you ready for the reality check? That's right. Life with a Brompton is not all spring days, palm trees, and umbrellas in my drinks. Folding/unfolding the Brompton, even after a month of continuous ownership, remains a challenge for me (though not for Rick). Electronic buttons or other high-tech Transformers-like miracles are absent. And no combination of magic words, from "Wonder Twins, activate!", to "Ready, Set, Go!" will work. You must fold the bicycle yourself, step-by-step, in the proper order. Or you will not fold the bicycle. To carry a Brompton that you failed to fold correctly is like carrying a reluctant dog to the vet. It has other ideas, and being carried is not one of them. Folding one is so tricky that there are numerous videos claiming to demonstrate the ease of folding the bicycle. Some run twenty seconds or more. That said, Rick folds it up in a blink.

Also, the bicycle is not a featherweight. It weighs as much as my big bike. About 26 pounds. Picking up a 26-pound square of folded metal that has been on the street is not easy, nor necessarily clean. Heaving it up and down the steps of a Rapid bus (Los Angeles) or Metro traincar (Denver) is rough. Especially if you are trying to keep it away from your clothes. I recommend that you keep a soft, absorbent towel and a few handy wipes with you. Still, no worse than a big bike.

The drivetrain works just okay, with louder than usual "ticking" as you ride, and some hesitation on one particular shift position.

In summary, I am very happy with my breezier Brompton life. Its open geometry and low profile make getting on and off easy, even in office clothes. Tucking it away is wonderful. If parts of your life are anything like what I have described above, then I recommend it as a primary or secondary bicycle.

Here are the specifications on the Brompton I rode on the recent train trip:

- M6L in Turkish Green

- 6-speed wide range drivetrain (2-speed derailleur + 3-speed internal)

- Brooks B-17 saddle

- Fenders

- 16" Schwalbe Marathon tires

- Shimano dynohub with Busch & Müller head and tail lamps

- S-bag front-mounted messenger-style bag, with compartments

In booking that traverse—a beautiful run across spectacular Western landscapes, including Donner Pass—I had made a modest error. Trusting only to vague memory, I'd assumed that Amtrak's Emeryville station was across from a BART stop. However, I was wrong; it's the Richmond station that is across from the BART stop. The nearest BART stop to Emeryville is some two or three miles off. After getting some rather inadequate directions from the snack-bar cashier in the station, we set off on a complicated route. Later, when I was back in the East Bay to visit my colleague Chris Kidd, formerly of LADOT and now with Alta Planning, Chris told me about a wonderful bike route between the Amtrak station and the BART stop, one which is visually delightful, quiet, and often runs on off-street paths. But we took the dull, noisy, car route over to the MacArthur BART stop, with the Bromptons slipping cheerfully through the traffic and of course fitting easily into the spacious BART cars. BART restricts the boarding of full-sized bikes in certain stations at certain times, but folders are free to climb on anywhere no matter what the hour.

So soon we were in San Francisco, wending our way from the Civic center BART stop to the little inn that Gina favors in the Fillmore District. Once there, the bikes folded up again to live in a nook of the garage, ready to roll out into the alley and face the city's hills.

The next day I rolled down to the Embarcadero and hopped back on BART to Oakland. I pedaled along the borad, busy streets as far as Berkeley, where I met Chris Kidd for lunch and an update on the area's bikeways. Of course I explored said bikeways on my way back to Jack London Square, where I boarded the Oakland-Alameda ferry for the ride back to the Embarcadero. I didn't bother folding the Brompton all the way—swinging the rear triangle under brings the little idler wheels into play as a sort of prop stand; looks odd but works well most of the time. With the front wheel jammed into a corner (ferryboat bike racks are not of the best) the bike was perfectly stable even when the boat was not. Indeed, the novelty of the bike was wearing off for me, and it was becoming a very useful tool for getting around in a complicated and crowded city.

Back into traffic and up the easy hills to the Fillmore and dinner with Gina, ending the day.

The next day saw me plunge into the traffic chaos of SoMa to visit acquaintances at Public Bikes before backtracking nearly to Chinatown to meet pal Eric A. for lunch at Café de la Presse. That corner is one of the few lacking bike racks in the downtown area, so, acutely aware that I was riding a borrowed titanium bike, I folded the little fellow all the way and stowed him under the table. Eric showed up on a Big Dummy with two child seats and his littler girl along, the other seat waiting till he dropped by school on the way home to Noe valley to pick up the older daughter. Although he kept glancing out the window to check on his bike, I was not that happy to have the Brompton underfoot; indeed, I find that I prefer to leave my bike outside when I am at a restaurant or store. Bromptons are difficult to lock up, and their portability is touted as a solution to theft worries, but there are many, many situations in which you might not want to haul around twenty-five pounds of bike, no matter how compactly folded, as you wander through a department store, museum, or crowded restaurant. I don't suppose most museums would even allow you to.

After lunch, Eric and I briefly toured SoMa, especially the waterfront and stadium areas. Our two steeds certainly represented extremes of bicycle design, and we must have made an odd couple indeed as we rolled around the sunny streets.

The next day, Gina finally escaped the client site by noon, and after a lunch in the Fillmore we got both Bromptons out for a spin across the Golden Gate Bridge to Sausalito. The wind was harsh, and there were, despite my efforts at planning an easier ride, some decidedly steep hills. On the bridge itself, the wind came from abeam and was quite gusty, but the little Bromptons didn't let it push them around. The crossing was uneventful in a velocipedal sense, though of course spectacular as a sensual and visual experience, a far better way to understand the bridge and the bay than plowing across it in a car. We stopped halfway across simply to savor the moment more fully, looking down at the hard distant water that reached across the planet to Japan while the wind boomed in our ears and tore at our hair. And then we saddled up and pedaled unremarkably onward to the Marin County side of the Golden Gate.

A winding steep descent took us under the bridge and to a road that followed the bayshore, rising and falling with the hill of the high bluff. The weather immediately became warmer and sunny, while the bridge behind us was still wreathed in scraps of fog. A few more winding turns through forested slopes, and an easy flat pedal along a road barely two feet above the softly-lapping wavelets of the bay, brought us to Sausalito. We cruised around for a while, found a homey Italian restaurant where we could restore ourselves with fine craft beers—this was the only time we actually locked the bikes outside in the Bay Area—and then headed back to the ferry landing we'd passed earlier. The Sausalito ferries can hold up to 130 bicycles, and are often close to full, as was the case that day. But there was no problem fitting the little Bromptons in.

Once back at the Embarcadero, we returned to Market Street and its very fine bike lanes, albeit bike lanes officially shared with taxis. The Bromptons made quick work of the traverse to Fillmore Street.

The next morning was another round of Market Street, BART, the wonderful bike path through Emeryville to the Amtrak station, and then onto the Coast Starlight for a leisurely, companionable ride home along the California coastal hills and beaches. We were old hands at travelling with the Bromptons by now, and when we arrived at Union Station in Los Angeles, we blossomed them into bikes again, rolled them to the subway, and then rode the last few miles home in the cool evening of late spring in Southern California.

A day or two later I returned the one I had ridden to Golden Saddle. But Gina's cheerful little blue M6 stayed home: she had decided to buy it for herself.

And it has proved useful, as Gina doesn't like the mad miles I dote on. Last ight, she packed the Brompton into her Mini Cooper when she left for a client site visit in Century City, then, after work, rode it to Wilshire we she took it on a 720 Rapid bus through the evening traffic crush to Santa Monica. There, I met her with my Bottecchia, whence we rode together to a book signing at Caffe Luxxe on Montana Avenue and left the bikes locked up while we ate dinner, after which we rode together back to Santa Monica Boulevard. From there, the #4 bus took Gina and Brompton back to Century City while I shot through the night on half-empty streets towards home on my lovely little fixie. An odd sort of togetherness, but it works...thanks to the Brompton.

Summary

Both Bromptons came with the clever six-speed drivetrain that combines a two-speed derailleur hub with a three-speed wide-range internal made to Brompton's specifications. Brompton also offers single-speed, two-speed, and three-speed versions. The six-speed reminded me of the half-step drivetrain on my old Bridgestone RB-T, a bike on which I put many happy miles. Gina found herself adapting to it readily as well. Gina's M model gave her a fairly upright riding posture, whereas the S model I rode was sportier, which i prefer anyway. In windy San Francisco I was truly grateful for the lower handlebars of the S type!

The fold is identical for all Brompton models, and once you learn it is very quick. Bromptonistas often fold the bike partway, when it becomes its own prop stand. Once a Brompton is folded properly, you can pick it up, swing it around, or stow it upright or on its side, and it won't unfold. It's very easy to lift or carry when folded.

Unfolded, the bikes rode quite well, though I did not find myself preferring the Brompton's ride to that of my usual bike, a 1960s Bottecchia Professional converted to a racked and fendered fixed gear. The low-trail steering is quite light, but we both became habituated to it within a few minutes, and had no trouble switching back to our usual bikes after nearly two weeks of riding only the folders. I put a large Carradice saddlebag on mine, and Gina used a front-mounted Brompton bag that clicks on and off and coverts to a satchel, and which she also bought after the trip. Our longest single days' distance with the Bromptons was around thirty miles, but we've been on a 55-mile group ride that included a Brompton ridden by a British traveler who joined up with us at the last minute, in Portland, and he had no trouble keeping up with a group that was largely on road bikes and randonneuses. All in all, we found them to be excellent travel bikes, and equally useful in town as multi-modal commute bikes. They are very well made, and many of the components are either made by Brompton in their factory, or—like the internal hub— made to the company's particular specifications.

All in all, an excellent choice for travel, commuting, or small apartments.

For technical details, visit the Brompton website.

Text & photos by Richard Risemberg, except photo of the author by Eric Anschutz